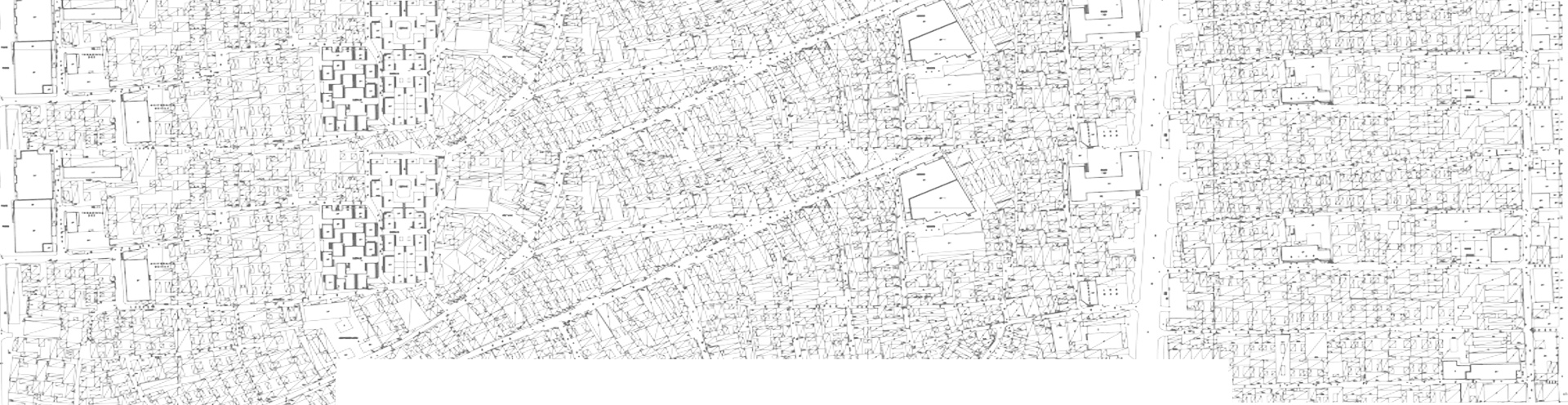

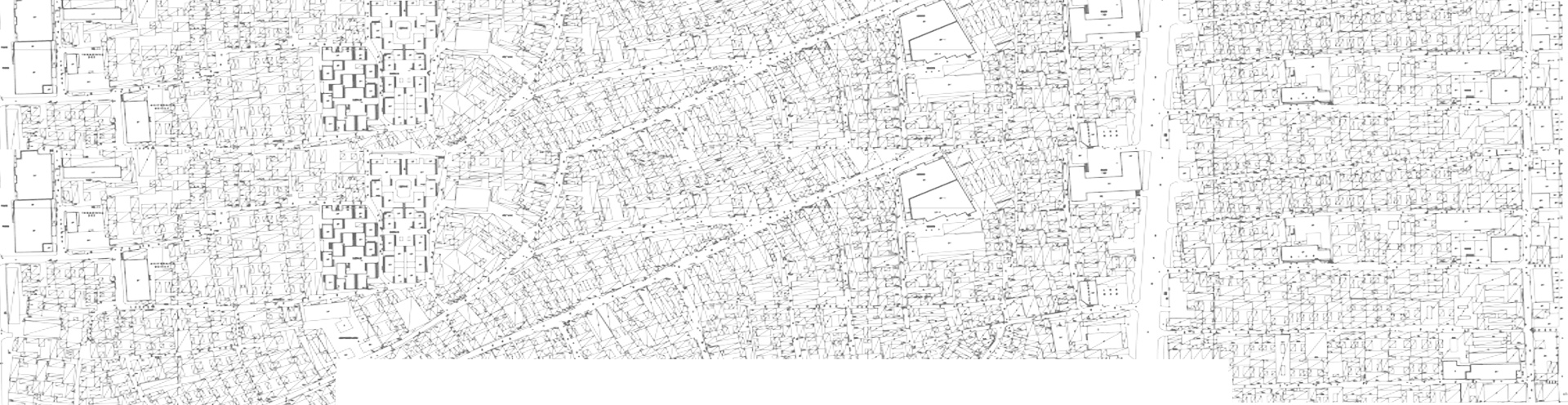

ABSTRACT 摘要Temples, in the past, had a priority over other types of buildings in most ancient cultures. 在过去的大多数古代文化中,寺庙建筑要优先于其他类型的建筑物。However, in the early ages of monotheistic religions, religious buildings were considered merely as gathering places for people to pray.在一神论宗教的早起,宗教建筑仅被视为人们祈祷的聚集地。 However, throughout history, sacred meanings were ascribed to ‘monotheistic temples’ and they have now transformed into spaces where religious authority is legitimated. 但是,纵观历史,神圣的含义被赋予“一神庙”,并且现在它们已转变成宗教权威得以合法化的空间。Thus, monotheistic temples were dissociated from other buildings like their ancient counterparts. 因此,一神殿与古代建筑一样与其他建筑分离。Likewise, it can be said that religious authority is dissociated from congregation.同样,可以说宗教权威与会众是分离的。System’s continuity depends on the potential energy difference between authority and congregation, which is highly undesirable for the profane world. 系统的连续性取决于权威与会众之间潜在的能量差异,这对于粗俗的世界来说是非常不利的。This situation provides some privileges to authority but in return authority has to legitimize its existence continuously. 这种情况为权威提供了一些特权,但同样的,权威必须不断使它的存在合法化。Although the distinction between sacred and profane exists, the situation is a gameplay in today’s rather secular world.尽管存在神圣与粗俗之间的区别,但在当今相当世俗的世界中,却是另外一种情况。Intersection between authority and congregation is mostly visible when rituals take place, and space becomes the field of the game. 举行仪式时,权力与会众之间的交汇处最为明显,而空间成为仪式的领域。Sequences of space and sequences of events are normally independent systems. 空间序列和事件序列通常是独立的系统。If sequences of events are liable to predefined programs, then components of the space become a ‘decoration’.如果事件序列属于预定义的程序,则空间的组成部分将成为“装饰”。In fact, religious rituals are strictly defined programs and enforce their existence over space. 实际上,宗教仪式是严格定义的程序,并在空间上强制其存在。This way, space becomes an instrument for authority to legitimize their power. 这样,空间成为授权使其权力合法化的工具。Moreover, configuration of the space becomes a component of the power game.而且,空间的配置成为权利游戏的组成部分。In this paper, the relation between religious authority and congregation is analysed during rituals, grounded on cross readings of syntactic and observation data. 本文基于对句法和观察数据的交叉解读,分析了仪式中宗教权威与会众之间的关系。Four actively used temples located in Istanbul have been chosen to be observed: a synagogue; an Assyrian church; a mosque: and an Alevi cemevi. 选择了位于伊斯坦布尔的四个活跃使用的庙宇:一个犹太教堂;一个亚述教会;一个清真寺:还有土耳其教堂。Spatial potentials of these temples are compared to each other for religious authority and congregation respectively.比较这些庙宇的空间潜力,分别比较其宗教权威和会众。The aim is to attempt to understand if monotheistic religions’ understanding of power and authority reflects their space configuration. 目的是试图了解一神教徒对权力和权威的理解是否反映了他们的空间配置。Indeed. nuances have been observed between temples spatial configuration and the understanding of power which is semantically valuable.确实。已经观察到寺庙空间配置和对力量的理解之间的细微差别,这在语义上是有价值的。

2021-01-09REFERENCES 参考文献1. Al Sayed K., Turner A., Hillier B., Lida S., Penn A., 2014, Space Syntax Methodology , 4thEdition, Bartlett School of Architecture, London2. Baştürk E., Bir Kavram İki Düşünce: Foucault‟dan Agamben‟e Biyopolitikanın Dönüşümü:Alternatif Politika, 2013, Volume 5, Issue 33. Benedikt M.L., To Take Hold of Space: Isovists and Isovist Fields, 1979, Environment andPlanning B, 6. Issue4. Düzenli B., Laleli Camii ve Külliyesi, 2003, Ebû‟l-Vefâ Vakfı5. Dovey K., Framing Places, Mediating power in built form, 2008, Routledge, London and NewYork6. Edgü E., Konut Tercihlerinin, Mekansal Dizim ve Mekansal Davranış Parametreleri ile İlişkisi,2003, İstanbul Technical University, PhD dissertation, İstanbul.7. Eliade M., The Sacred and the Profane, The Nature of Religion, 1963, New York8. Foucault M., Özne ve İktidar, 2016, İstanbul, 5th Edition9. Frishman M., Islam and the Form of the Mosque, 1994, London10. Hanson J, The architecture of justice: iconography and space configuration in the English lawcourt building, 1996, Theory, London11. Hart R.A., Moore, G.T., The Development of Spatial Cognition: A Review, Graduate School ofGeography and Department of Psychology, Clark University, 197112. Hillier B., Hanson J., 1984, The Social Logic of Space, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge13. Hillier, B., Penn, A., Hanson, J., Grajewski, T., Xu, J., 1993, Natural Movement or Configurationand Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement, Environment and Planning B: Planning andDesign 14. Keskin F., Foucault’da Özne ve Öznellik, Toplum ve Bilim Magazine, Issue 73, 199715. Khan H. U., The Architecture of the Mosque: An Overview and Design Directions16. Kilde J. H., Sacred Power Sacred Space, An Introduction to Christian Architecture and Worship, 2008, Oxford University Press17. Kuban D., Batıya Göçün Sanatsal Evreleri, 1993, İstanbul18. Özdel G., Foucault Bağlamında İktidarın Görünmezliği ne “Panoptikon” ile “İktidarın Gözü” Göstergeleri, 2012, Volume 219. Olsen M., Forms and Level of Power Exertion, in M. Olsen and M. Marger (eds),1993, Power in Modern Societies, Boulder, CO:Westview 20. Özel K., Dini Mimaride Merkez Kavramı: Tapınma Mekânına „Merkez‟ Kimliği Kazandıran Öğeler, 1998, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Master’s Thesis, İstanbul 21. Şahin M. S., “Yahudilik”, Şâmil İslâm Encyclopedia, İstanbul, 1994, VI 22. Tanman B., Dünden Bugüne İstanbul Encyclopedia, İstanbul, 1994, VII23. Tschumi B., Ritual, The Princeton Journal, Thematic Studies in Architecture, Volume 1, 198324. Ünlü A., Çevresel Tasarımda İlk Kavramlar, 1998, İstanbul25. Wrong D., Power, 1979, New York, Harper and Row.26. Yaxley N., A Design Narrative: Design Intent, Perception, Experience and a Structural Logic of Space, 2014

2021-01-09